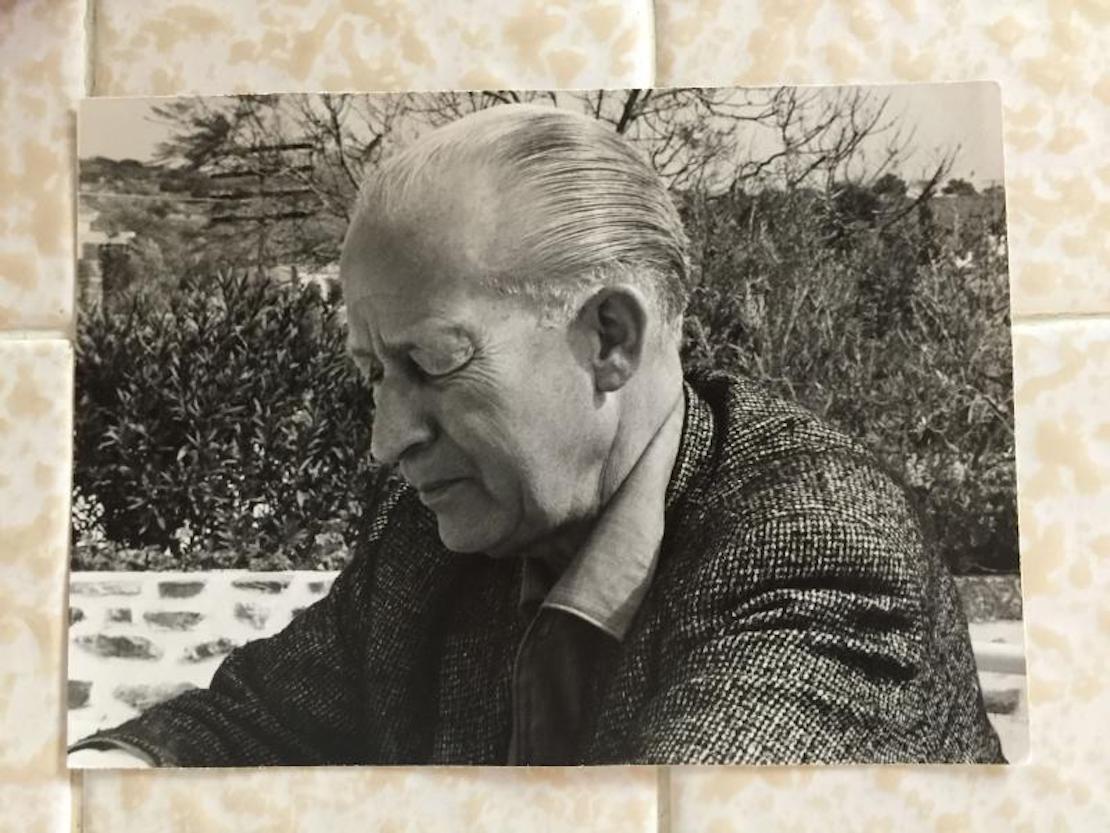

Julius de Clercq Zubli

Background to the Crisis

The Netherlands (Holland) was occupied by Nazi Germany in May 1940, during the blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) in which Germany occupied Norway and Denmark (April), Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg (May), and France (June).

The first anti-Jewish measures began in Holland in June 1940. By November all Jews had been removed from public positions, including universities, which provoked student protests in Leiden and elsewhere. In early 1941, as Jews in Holland were increasingly segregated from the general population and Dutch workers were threatened with forced labor in Germany, strikes and protests began, and the outlawed Communist Party in the Netherlands called for a general strike on February 25, 1941.

De Dokwerker (The Dockworker) in Amsterdam, commemorating the February 25, 1941 strike

Other protests and resistance followed. When told that they had to join the German doctors’ guild, which would have forced them to follow Nazi guidelines for racial screening and prevented them from treating Jews, thousands of Dutch doctors signed a letter of protest in December 1941. Many doctors gave up their practice, or treated patients in secret. One group of doctors formed an organization to provide safe hiding places for physicians under attack by German police.

On March 25, 1943, more than 6,200 Dutch physicians—97 percent of the country’s doctors—went on strike against an order for all physicians to join the Nazi-created Chamber of Physicians. Hundreds of the protesters were arrested, and for weeks there was almost no medical service in the Netherlands. Only the threat of epidemic disease persuaded the Nazis to rescind the order.

Additional Information about the Rescuers

Zubli, who was not Jewish, had a permit to be out after curfew. This enabled him to provide (illegally) medical and other services to Jewish patients as well as to members of the Dutch resistance.

Zubli was one of the few doctors who refused to shut down his medical practice or to participate in 1943 strike of Dutch doctors. He believed that his oath as a physician required him to provide medical services to anyone who needed his help—even Germans.

After his arrest, Zubli’s wife Ellie saved his life by putting on her finest dress and hurrying to police headquarters to retrieve the patient notebook her husband always carried with him. She told the Gestapo agents that the book was needed by the doctor who would treat Dr. Zubli’s patients in his absence. After checking the book several times, they gave it to her. In fact, the book contained code names of members of the Dutch resistance as well as details of escape routes throughout Europe—information that, had it been discovered, would have led to Zubli’s execution.

Julius Zubli's jacket from Sachsenhausen (Permanent Collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Julius and Ellie Zubli

Julius Zubli's identification bracelet from Sachsenhausen (Permanent Collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

An unpublished memoir by J. Gerber, a prisoner in Sachsenhausen concentration camp, recounts how Zubli and another doctor provided medical assistance to their fellow prisoners with no facilities or supplies. He describes him as “a completely noble person, something of which he himself is unaware.” Zubli also organized a concert on Christmas Day 1944 for his patients in Sachsenhausen with a Jewish violinist and flutist; prisoners sang a few songs written by Zubli himself.

The Zublis’ three children were aware that their father was involved in mysterious activities during the occupation, but when they asked questions he told them that he would explain everything after the war. After he returned from Sachsenhausen to Amsterdam, he told them, “I have only done my duty,” and said almost nothing more about what he had done.

Timeline

1899 (June 5) Born in Palemberg, Sumatra, Dutch East Indies

1926 Receives his medical degree from the University of Leiden

1942 In the summer, as deportations begin, starts supplyig false food stamps, obtained from a local resistance group, to people in hiding

1944 (May 3) Treats the wounded resistance fighter Gerrit van der Veen; (May 9) while Zubli is visiting van der Veen, both are arrested by the Gestapo

1944 (July 6) Sent to Vught concentration camp and subsequently ti Sachsenhausen concentration camp

1945 Liberated from Sachsenhausen, returns to Amsterdam and restarts his medical practice

1967 (April 14) Dies in Amsterdam

2001 (March 18) recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations; (6 May 2002) honored at ceremony at the Embassy of Israel in Washington, DC

Primary and Other Sources

Bremer, Georgette G. “Holocaust savior honored in Washington.” The Acorn, 30 May 2002. http://www.theacorn.com/news/2002-05-30/Community/032.html

Bush, Lawrence. “March 25: Doctors Strike Against Nazism.” Jewish Currents: Activist Politics and Art. 24 Mar. 2012. http://jewishcurrents.org/march-25-doctors-strike-against-nazism/

Musynske, Gavin. "Dutch Citizens Resist Nazi Occupation, 1940-1945." Global Nonviolent Action

Database. Ed. Max Rennebohm. Swarthmore College, 09 Nov. 2009. http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/dutch-citizens-resist-nazi-occupation-1940-1945

Yad Vashem. “The Righteous Among the Nations: Julius Karel Isaac de Clercq Zubli.” http://db.yadvashem.org/righteous/family.html?language=en&itemId=4408736